- November 22, 2025

- GitHub

Table of Contents

Toggle🏡 House Price Prediction: A Complete Machine Learning Journey

Predicting house prices is one of the most practical and engaging applications of machine learning. In this comprehensive project, I embarked on a journey to build accurate predictive models for the Kaggle competition: House Prices: Advanced Regression Techniques. This challenge involves predicting sale prices of homes in Ames, Iowa, based on 79 explanatory variables describing various aspects of residential properties.

Now what makes this project particularly interesting is the emphasis on feature engineering. The process of transforming raw data into meaningful features that can dramatically improve model performance. Throughout this journey, I analyzed 79 different features, engineered new ones, handled missing values intelligently, and applied advanced techniques like stacking and ensembling to achieve optimal results.

Beyond being an excellent learning exercise, house price prediction has real-world applications:

- Real Estate Valuation: Automated property valuation helps buyers and sellers make informed decisions

- Investment Analysis: Investors can identify undervalued properties and market trends

- Urban Planning: Understanding price determinants aids in city development and policy making

- Mortgage Lending: Banks use predictive models for risk assessment and loan approvals

Project Roadmap

This blog post documents my complete journey through the following 13 major steps:

Step 1: Importing Libraries and Datasets

Setting up the environment with essential Python libraries for data manipulation, visualization, and machine learning.

Step 2: Dataset Visualization

Initial exploration to understand the structure, distributions, and characteristics of the data.

Step 3: Separating ID Column

Handling identifier columns that do not contribute to predictions.

Step 4: Removing Outliers

Identifying and removing anomalous data points that could negatively impact model training.

Step 5: Normalizing Label Column

Transforming the target variable (SalePrice) to improve model performance.

Step 6: Concatenating Train and Test Datasets

Combining datasets for unified preprocessing and feature engineering.

Step 7: Dealing with Missing Values

Comprehensive strategy for handling missing data across different feature types.

Step 8: Feature Engineering

The largest and most critical section, creating new features and transforming existing ones.

Step 9: Handling Skewness

Applying transformations to reduce skewness in feature distributions.

Step 10: Recreating Train & Test Datasets

Separating the processed data back into training and testing sets.

Step 11: Regressor Models Implementation

Training multiple machine learning algorithms, hyperparameter tuning, stacking, and ensembling.

Step 12: Deep Neural Network Implementation

Building a custom DNN using the low-level APIs of TensorFlow with regularization and optimization.

Step 13: Conclusion

Synthesizing results, key learnings, and future directions.

1 Importing Libraries and Datasets

Every data science project begins with setting up the proper environment. For this house price prediction task, I needed a comprehensive toolkit spanning data manipulation, statistical analysis, visualization, and machine learning algorithms.

Core Libraries

The foundation of any Python-based data science project consists of several essential libraries:

import numpy as np import pandas as pd import matplotlib.pyplot as plt import seaborn as sns from scipy import stats from scipy.stats import norm, skew # Set visualization style sns.set_style('whitegrid') plt.rcParams['figure.figsize'] = (12, 8)

- NumPy: Fundamental package for numerical computing, providing efficient array operations

- Pandas: Data manipulation and analysis library with DataFrame structures

- Matplotlib & Seaborn: Visualization libraries for creating insightful plots and graphs

- SciPy: Scientific computing tools including statistical functions and tests

Machine Learning Algorithms

The project utilizes a diverse array of regression algorithms from scikit-learn, each with unique strengths:

from sklearn.linear_model import ( ElasticNet, Lasso, BayesianRidge, LassoLarsIC, Ridge ) from sklearn.ensemble import ( RandomForestRegressor, GradientBoostingRegressor, StackingRegressor ) from sklearn.kernel_ridge import KernelRidge from sklearn.pipeline import make_pipeline from sklearn.preprocessing import RobustScaler from sklearn.model_selection import ( KFold, cross_val_score, train_test_split, GridSearchCV ) from sklearn.metrics import mean_squared_error import xgboost as xgb import lightgbm as lgb

Ridge, Lasso, ElasticNet: Regularized linear regression models that prevent overfitting by penalizing large coefficients.

Random Forest, Gradient Boosting: Combine multiple decision trees to create powerful predictive models.

XGBoost, LightGBM: State-of-the-art implementations optimized for speed and performance.

Stacking: Meta-learning approach that combines predictions from multiple base models.

Loading the Dataset

The Kaggle competition provides two CSV files: a training set with known sale prices and a test set for which we need to predict prices.

# Load training and test datasets train = pd.read_csv('train.csv') test = pd.read_csv('test.csv') # Display basic information print(f'Training set shape: {train.shape}') print(f'Test set shape: {test.shape}') print(f'\nFirst few rows of training data:') print(train.head())

2 Dataset Visualization & Initial Exploration

Before diving into modeling, it is crucial to understand the structure, distributions, and relationships in data. This exploratory phase reveals patterns, anomalies, and insights that guide subsequent preprocessing decisions.

Understanding the Target Variable: Sale Price

The first priority is understanding what we are trying to predict. Let us examine the distribution of house sale prices:

# Descriptive statistics print("Sale Price Statistics:") print(train['SalePrice'].describe()) # Visualize distribution fig, axes = plt.subplots(1, 2, figsize=(14, 5)) # Histogram with KDE sns.histplot(train['SalePrice'], kde=True, ax=axes[0]) axes[0].set_title('Sale Price Distribution') axes[0].set_xlabel('Sale Price ($)') # Box plot to identify outliers sns.boxplot(y=train['SalePrice'], ax=axes[1]) axes[1].set_title('Sale Price Box Plot') axes[1].set_ylabel('Sale Price ($)') plt.tight_layout() plt.show()

Feature Type Classification

Understanding which features are numerical versus categorical is essential for appropriate preprocessing:

# Separate numerical and categorical features numerical_features = train.select_dtypes( include=['int64', 'float64'] ).columns.tolist() categorical_features = train.select_dtypes( include=['object'] ).columns.tolist() # Remove Id and SalePrice from numerical numerical_features.remove('Id') if 'SalePrice' in numerical_features: numerical_features.remove('SalePrice') print(f'Numerical features: {len(numerical_features)}') print(f'Categorical features: {len(categorical_features)}')

Correlation Analysis

Understanding which features correlate strongly with sale price helps prioritize feature engineering efforts:

# Calculate correlations with SalePrice correlations = train[numerical_features + ['SalePrice']].corr() saleprice_corr = correlations['SalePrice'].sort_values( ascending=False ) # Display top correlations print("Top 10 features correlated with SalePrice:") print(saleprice_corr[1:11]) # Visualize correlation heatmap top_features = saleprice_corr[1:11].index.tolist() + ['SalePrice'] plt.figure(figsize=(12, 10)) sns.heatmap( train[top_features].corr(), annot=True, fmt='.2f', cmap='coolwarm', center=0 ) plt.title('Correlation Matrix of Top Features') plt.show()

- Overall Quality (0.79): Material and finish quality of the house

- Above Ground Living Area (0.71): Square footage of living space

- Garage Cars (0.64): Size of garage in car capacity

- Garage Area (0.62): Size of garage in square feet

- Total Basement SF (0.61): Total square feet of basement area

- 1st Floor SF (0.61): First floor square feet

- Full Bath (0.56): Full bathrooms above grade

- Total Rooms Above Grade (0.53): Total rooms excluding bathrooms

- Year Built (0.52): Original construction date

- Year Remodeled (0.51): Remodel date

- Quality metrics (OverallQual) show the strongest correlation, emphasizing that quality matters more than quantity

- Living area dimensions are highly predictive, but with diminishing returns (potential non-linear relationships)

- Year features indicate age affects value, suggesting newer homes command premium prices

- Multicollinearity exists between related features (e.g., GarageArea and GarageCars) that is important for linear models

- Categorical features like Neighborhood, ExterQual, and KitchenQual likely contain significant predictive power not captured in numerical correlations

3 Separating ID Column

Before proceeding with any analysis or modeling, it is important to handle identifier columns that do not contribute to predictions but serve as reference markers.

# Store IDs for later use in submissions train_id = train['Id'] test_id = test['Id'] # Drop Id from datasets train = train.drop('Id', axis=1) test = test.drop('Id', axis=1) print(f'Training set shape after removing Id: {train.shape}') print(f'Test set shape after removing Id: {test.shape}')

4 Removing Outliers: A Systematic Approach

Outliers are data points that significantly deviate from other observations. They can dramatically affect model training, especially for linear models that minimize squared errors. However, outlier removal must be done carefully. Often times, what appears as an outlier might be a legitimate high-value property or a unique architectural feature.

The Outlier Detection Strategy

My approach to outlier detection was systematic and multi-faceted:

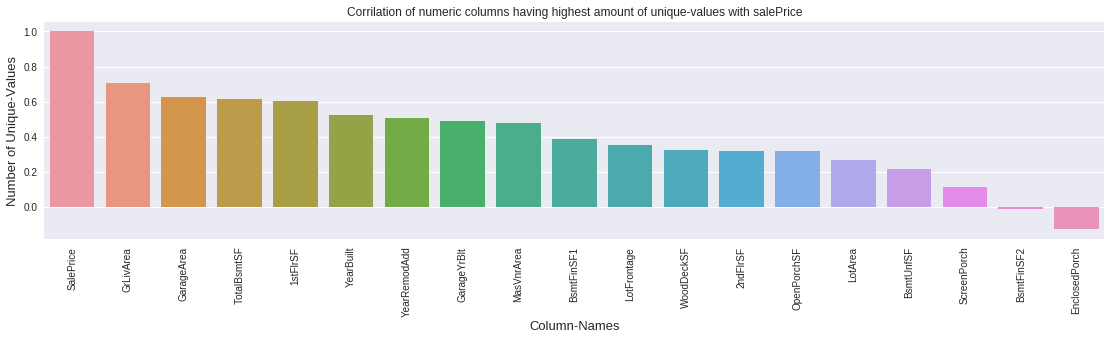

Step 1: Focus on High-Information Features

Prioritize numerical features with many unique values (high variance) that are also strongly correlated with sale price.

Step 2: Visual Inspection

Create scatter plots of each feature against sale price to identify points that deviate from the general trend.

Step 3: Test Set Validation

Verify that removed outliers don't represent common patterns in the test set—removal should only target true anomalies.

Step 4: Distribution Comparison

Compare feature distributions between train and test sets to ensure removal doesn't create distribution shifts.

Identifying Outlier Candidates

# Get numerical columns and count unique values numeric_cols = train.select_dtypes(include=[np.number]).columns unique_counts = {} for col in numeric_cols: if col != 'SalePrice': unique_counts[col] = train[col].nunique() # Sort by number of unique values (descending) sorted_features = sorted( unique_counts.items(), key=lambda x: x[1], reverse=True ) # Select top features with high variance high_variance_features = [f[0] for f in sorted_features[:19]] # Check correlation with SalePrice correlations = train[high_variance_features + ['SalePrice']].corr()['SalePrice'] print(correlations.sort_values(ascending=False))

Why focus on high-variance numerical features?

- Features with many unique values have higher probability of containing outliers

- Outliers in features strongly correlated with sale price have greater impact on model accuracy

- Categorical features with few levels are less susceptible to outlier effects

Creating an Outlier Detection Function

To efficiently analyze potential outliers across multiple features, I created a comprehensive visualization function:

def check_outliers(feature_name): """ Visualize potential outliers for a feature: 1. Test set scatter (are similar values present?) 2. Train/Test distribution comparison 3. Train set scatter against SalePrice """ fig, axes = plt.subplots(1, 3, figsize=(18, 5)) # Plot 1: Test set scatter axes[0].scatter( range(len(test)), test[feature_name], alpha=0.5 ) axes[0].set_title(f'{feature_name} in Test Set') axes[0].set_xlabel('Sample Index') axes[0].set_ylabel(feature_name) # Plot 2: Distribution comparison axes[1].hist(train[feature_name], bins=50, alpha=0.5, label='Train') axes[1].hist(test[feature_name], bins=50, alpha=0.5, label='Test') axes[1].set_title('Distribution Comparison') axes[1].legend() # Plot 3: Train set scatter vs SalePrice axes[2].scatter( train[feature_name], train['SalePrice'], alpha=0.5 ) axes[2].set_title(f'{feature_name} vs SalePrice (Train)') axes[2].set_xlabel(feature_name) axes[2].set_ylabel('SalePrice') plt.tight_layout() plt.show()

Case Study: Removing Outliers from Ground Living Area

Let me walk through a specific example—Ground Living Area (GrLivArea), which measures the above-grade living space in square feet:

# Visualize GrLivArea check_outliers('GrLivArea') # Identify outliers: large GrLivArea but low SalePrice outliers_grlivarea = train[ (train['GrLivArea'] > 4000) & (train['SalePrice'] < 300000) ] print(f'Found {len(outliers_grlivarea)} outliers in GrLivArea') print(outliers_grlivarea[['GrLivArea', 'SalePrice']]) # Remove outliers train = train.drop(outliers_grlivarea.index) print(f'\nNew training set size: {train.shape[0]}')

- Data entry errors

- Properties with specific issues (structural problems, poor locations)

- Incomplete sales or foreclosures

Since no similar extreme values exist in the test set and these points deviate significantly from the general trend, removing them improves model generalization.

Systematic Outlier Removal Across Multiple Features

I applied similar analysis to several key features:

Removed: 1 sample with exceptionally high first floor area but low price

Impact: 0.07% of training data

Removed: 1 sample with >2000 sq ft finished basement but low price

Impact: 0.07% of training data

Removed: 4 samples with >80,000 sq ft lot but low prices

Impact: 0.27% of training data

Removed: 2 samples with >4000 sq ft living area but <$300k price

Impact: 0.14% of training data